The Dutch States General

The States General was the political assembly of the United Provinces of the Dutch Republic between 1579 and 1795. The institution had its origin in the late medieval period, when the Dukes of Burgundy, and later their Habsburg successors, ruled as lords both of the Southern Low Countries (roughly present-day Belgium) and the Northern Low Countries (roughly corresponding to the current Netherlands). The first general assembly of this medieval version of the States General took place in the Flemish city of Bruges in 1464. During the Dutch Revolt (1568-1648), however, the northern provinces (Gelderland, Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Friesland, Overijssel, and later Groningen) wrested sovereignty away from their Catholic Habsburg overlord. The Union of Utrecht of 1579 was the founding moment when these provinces united to form the federated state known as the Dutch Republic. From then on, the States General was the chief political platform where representatives of these provinces met to discuss matters pertaining to the realm.

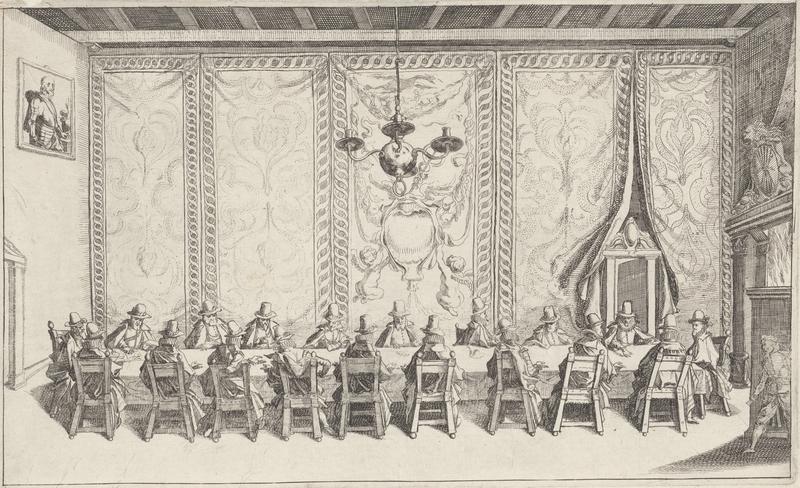

Meeting of deputies of the States General on the peace negotiations for the Twelve Years Truce, 6 February 1608. Etching by Simon Frisius, from: Scènes van de oorlog van 1608 en 1609 (series title). Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

And essentially, theirs was a Protestant polity. For one thing, the northern secession from the Habsburg state was primarily religiously-motivated. For another, besides their initial resistance against a joint oppressor, their shared religion and associated cultural values have been identified as the mortar that held the union together. For, otherwise, the provinces were only loosely tied to each other. In fact, following their resistance against the Habsburg prince, each individual province was sovereign within its own territory. Furthermore, in contrast to the general assemblies of other countries, such as the English Parliament, the States General consisted of representatives who were not standing ‘members’ of the assembly: these men were ‘deputised’ by their respective provincial Estates Assemblies. And they were not allowed to diverge from the specific voting instructions these provincial bodies imposed upon them. This difference from England was illustrated by the statesman Johan de Witt in a letter he wrote to a Dutch ambassador across the Channel in 1652. De Witt wrote:

“The English call these United Netherlands by the name Respublica, which is adjudged to be not quite proper, as these Provinces are not together una respublica, but each province separately a sovereign respublica. And, as such, these United Provinces should not be called by the name of respublica (in singulari numero), but rather with the name of respublciae foederatae or unitae, in plurali numero.” (Letter to Gerrit Schaep Pietersz., 10 May 1652)

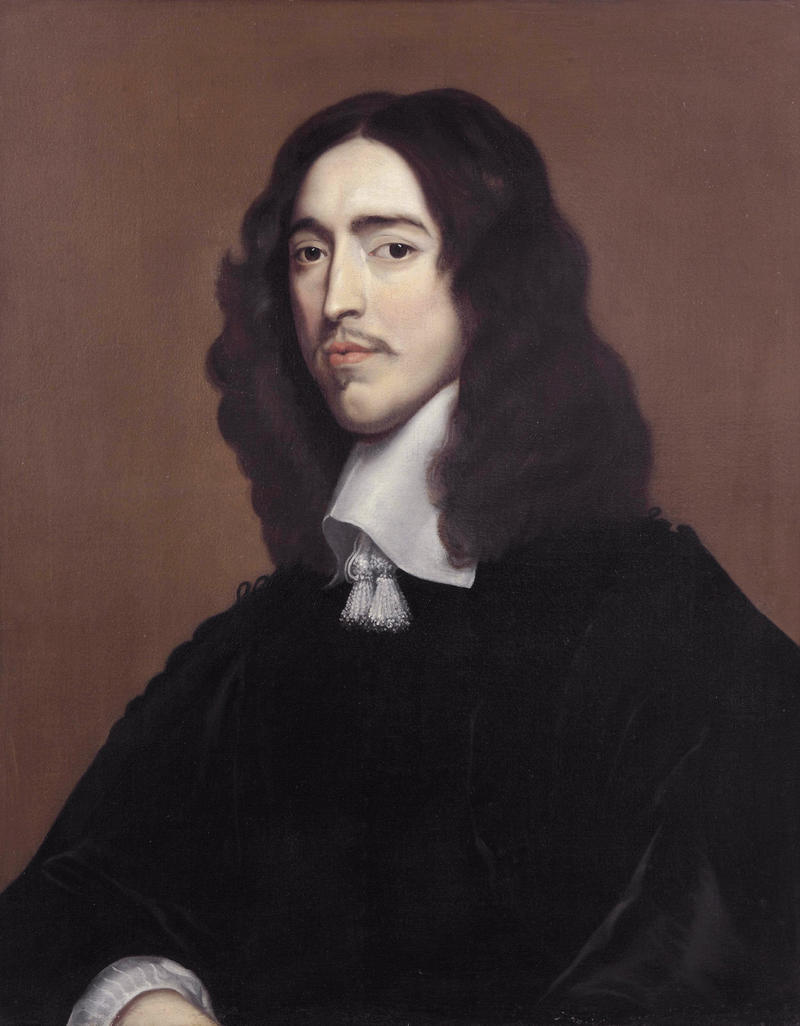

Portrait of Johan de Witt, Grand Pensionary of Holland. Anonymous painter, 1652. Wikimedia Commons.

This notion that people in other countries had erroneous perceptions about the nature of the States General’s sovereignty is counterbalanced by a contemporary awareness of transnational similarities in political culture. In fact, the 17th-century resolutions of the Dutch States General (comparable to the acts of the English Parliament) contain detailed considerations of how the deputies felt their own institution compared to general assemblies in other countries. In one such resolution of 1649, for example, Dutch ambassadors to foreign realms were instructed that they should act exactly like (and expect the same kind of treatment as) those of the Republic of Venice, which seems to have been something of a model as to how the Dutch Republic would like to be perceived in other countries.

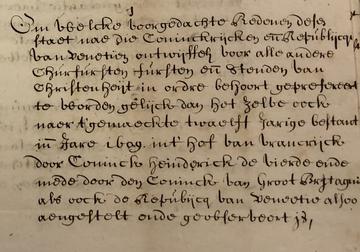

Detail of the 1649 ‘resolution’ of the Dutch States General drawing a comparison with the Republic of Venice. Nationaal Archief, The Hague.

Another similarity between the States General and other early modern European assemblies are shared cultures of record-keeping. Much like the German Imperial Diet and the English Parliament, the institution produced vast amounts of resolutions and other types of documents. And early modern Dutch deputies clearly deemed it important to care for their own archives. This is illustrated by material culture, such as this cabinet they had made specially to preserve the States General’s archives in the 17th century.

Cabinet formerly containing the archives of the Dutch States General, 17th century. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Of course, the parliamentary tradition of the Dutch States General also had features that were quite distinct from those in other countries. Perhaps the greatest contrast with other European countries was that sovereignty rested with this representative institution (or rather, as already mentioned, with the individual provinces) without the intercession of any king or prince. This had largely been the point of the Dutch Revolt, after all.

Nevertheless, the contemporary accounts of diplomatic relations between the States General on the one hand, and monarchs or political assemblies abroad on the other, demonstrate that even this republican outlier shared a common core of customs, rituals, and symbols with political administrations where sovereignty (partly) resided with royal rulers. When Charles II of England undertook an elaborate journey throughout the Dutch provinces just before the Restoration in 1660, for example, the monarch-to-be and the representatives who accommodated him smoothly engaged in shared political rituals like banquets and formal audiences. Bonifacius van Vrijberghe, one of the Dutch deputies to the States General who kept a diary during this time, commented upon his royal majesty respectful behaviour during his audience in the assembly’s Grand Chamber in The Hague:

“The King was given a seat at the centre of the table, under a velvet dais on an elevated footstool dressed with Turkish tapestries, on which was places a velvet armrest (this being the place where the presiding member of the [States General] is accustomed to sit, who for this one time took up a seat on the other side of the Table, right across from the King, where usually sit the ambassadors and other ministers whenever they are granted an audience). The King, then, having arrived at the aforesaid seat, remained standing bareheaded before his seat until all the members of the assembly had entered and had taken their seats. At that point, His Majesty sat down and put on his hat, just as the members of the assembly subsequently sat down and put on their hats”. (The Hague, Nationaal Archief, 2.21.005.39: Inventaris van het archief van I.J.A. Gogel, No. 164, fols 51r – 52 r.)

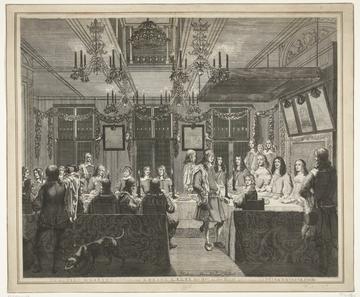

Banquet for the English King Charles II in the Mauritshuis in The Hague. Engraving by Pieter Philippe (after Jacob van Hoornvliet), 1660. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Huygens Institute of Netherlands History.